The Structure and Mysteries of the Story - How to Apply Storytelling to Your Project, Part 3

In the previous article Theme, Values and Morale Debate, we saw the importance of the message of your story, and how to send it properly — if you've not read it yet, I suggest you read it before this one since this is the continuation.

We have seen in this past article the importance of structure in exploring your moral debate.

In this article, we will have a look at the different types of structures that a story can be built with. But before this, I will introduce you to the base that all stories share.

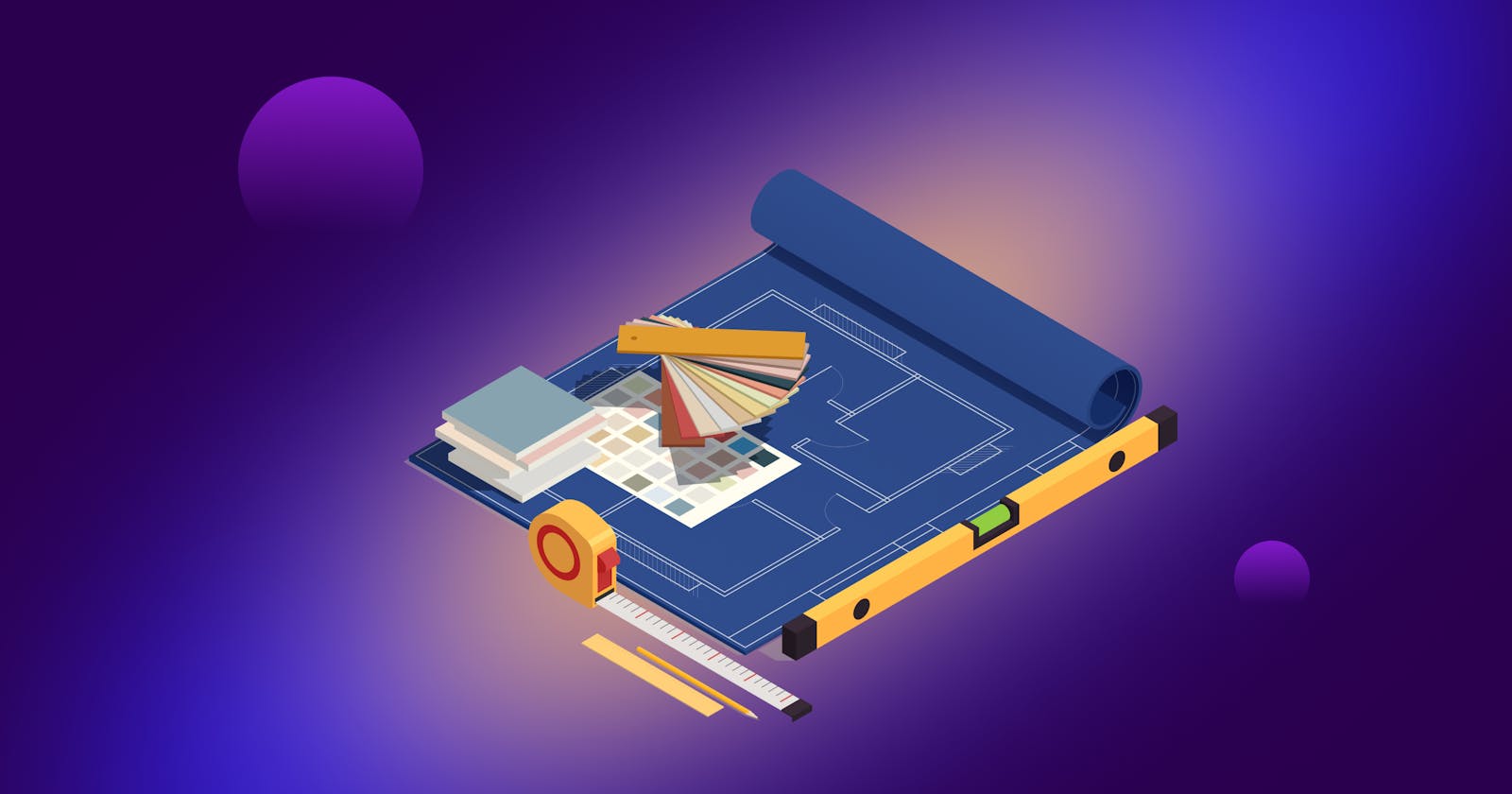

The story in 3 acts and the schéma quinaire

For centuries, narrators have agreed to decompose their stories into 3 acts.

The setup. This first act is made to set up your world, your main character, his goal, and the plot. It is considered as the act of presentation.

The confrontation. This second act is the longest one and is full of events. The most important event is the one during which your main character will realize that he can't reach his goal, and why.

The resolution. It is in this last act that your main character will succeed, or not, to reach his goal. More often, there is also a short epilogue showing the consequences of this story on your main character's life.

This very simple decomposition of the story will never be false and will always help you build a story with good bases.

However, we can also decompose a story into 5 parts.

The "schéma quinaire" — that we can translate as "the quinary scheme" — comes from the book L'analyse (morpho)logique du récit written by Paul Larivaille.

It's a school of thought that decomposes the story into 5 parts :

- The initial situation. The part in which the world and characters are introduced.

- The trigger. The part during which an event will disrupt the initial situation.

- The action. The part during which the main character will try to solve the disturbance.

- The resolution. The consequences of the actions.

- The final situation. The result of the resolution, leading to a new balance.

Moreover, Larivaille thinks also that it is possible to repeat a part multiple times. More often, the part repeated will be the action. By repeating this part, you can show how difficult it is for your main character to solve the disturbance.

Even though I've presented you with two different ways to decompose your story, it doesn't mean that you can't use both in your story.

In a way, they're very similar. The first act corresponds to Larivaille's initial situation, the second act corresponds to the trigger and the actions, and the third act corresponds to the resolution and the final situation.

- Key point: if you respect these parts or acts, your plot will naturally become more and more intense, until the climax.

The climax is the most important and exciting part of your story that happens at the end of the 2nd act (or during the 4th part). For example, in a superhero movie, it's the final battle between the hero and his enemy.

After this, in the 3rd act — or the 5th part — the intensity of your story falls back to the same level that it was at in the beginning of your story.

Now that you have the base, let's see different ways to structure your story.

The linear story

The linear story is the most common one. The main character pursues his goal with intensity until he has to frontally face his antagonist to reach it.

In this type of story, everything is clear. Goals, values, difficulties. It assures you to easily deliver the message of your story.

- Key point: a clear story doesn't mean a simplistic story. You can add a lot of complexity to your story outside than from the structure.

You can find this type of story in most Hollywood movies.

The linear story fits very well with projects that have a clear goal for their community. It will allow people to easily follow you in the story you will tell them, and play the part you want them to play.

However, if you want to develop a rich lore around your project, the linear story may not be your best option. It is too focused on one character, going straight to his goal without exploring many parts of his world.

The meandering story

Unlike the linear story, in the meandering one the main character doesn't pursue his goal with intensity, even though he has a clear one.

That is why he will encounter a lot of different people, generally, in a lot of different areas of the world you created — also named the "arena" by writers — and learn a lot about himself through the others. More often, this introspection leads the main character to reach his goal.

You can find this type of story in a lot of myths, like the Iliad.

The meandering story fits very well with projects that have a developed but finished lore. It will allow you to explore all the parts of your arena and go deeply into your main character's thoughts.

It is a good compromise if you want to develop a rich lore but still focus on the main character. Nevertheless, it may annoy your community to follow a character that doesn't pursue his goal with intensity.

You'll have to balance between exploring your lore and moving toward your character's goal.

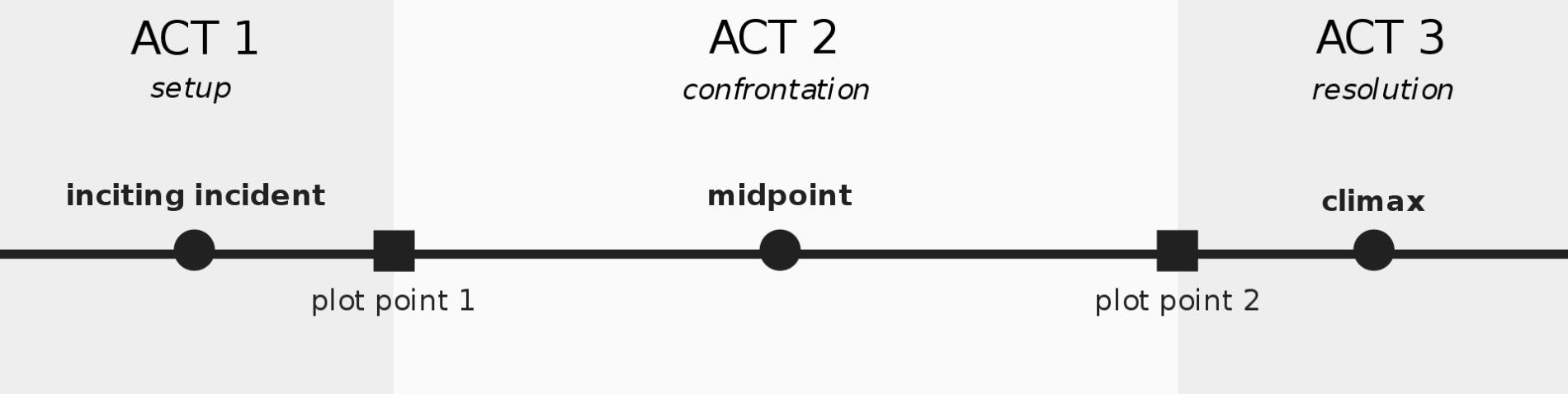

The spiral story

The spiral story is less common and probably less made for a project's storytelling.

In this type of story, the plot often comes from one particular moment that your main character will have to revive multiple times (through a dream for example) to understand and solve the mystery coming from this moment.

You can find this type of story in thrillers like Memento (Christopher Nolan, 2000).

This type of story fits perfectly with projects that rely on a mystery. However, your project can become a bit repetitive. You'll have to perfectly master the art of storytelling if you want to use this type of story.

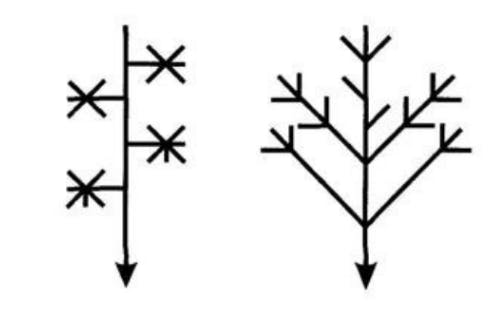

The branching story

In the branching story, each branch represents an entire society or a part of your lore's society.

This type of story is close to the meandering one, however, it's not necessarily centered on one main character traveling through the branches, it can be a separate story with whole new characters for each branch.

These stories must always be linked with the main story, like the trunk of a tree. Each story brings a piece that will help people understand and discover the main story.

You can find this type of story in spaces opera, or Gulliver's Travel (Rob Letterman, 2010).

The branching story fits very well with projects that develop complex lore that could be developed indefinitely. It will allow you to explore your entire lore and take time to go deeper into it. However, you will need a community that loves to discover because they could feel bored not following a character with a strong goal.

Nevertheless, it will allow you to tell multiple stories inside of the main one, so you can tell these stories in different ways and use the linear story to always catch your audience's attention.

The mysteries

Although all these structures are different, they share the same goal: exploit the mysteries of your story.

Because all the stories share at least one mystery: how will the main character reach his goal? This is the great mystery that your plot promises to answer. And before answering it, you will need to create other mysteries.

Mysteries are one of the keys to creating an interesting story, and it's even more important for a project's marketing. Marketing is supposed to captivate people and get them interested in your project. For this, presenting a story and promising mysteries around it is very efficient.

But as you've been able to read it, some structures exploit mysteries in a better way. For me, the best structure regarding this is the spiral one, even though I also think it is the hardest one to use to market a project.

On the other hand, the linear structure promises clarity and efficiency. But it doesn't mean that you have to rush from the beginning until the end. As said earlier in this article, most of the movies have a linear structure but are also full of mysteries.

- Key point: at the end of your story, all the most important mysteries have to be solved.

The unsolved mysteries can leave your audience wanting more, which is a good thing, but it can also leave an impression of something unfinished. It is really important to know which mysteries have to be solved, and which one can stay unsolved.

Also, it is important to give some keys to your audience to solve the mysteries. Not all of them, otherwise they'll guess the following of your story and thus lose all interest in it.

But if you don't give some of these keys, the revelations will seem inappropriate and spoil the audience's satisfaction.

Regarding a story, and mostly its structure and mysteries, it's all about balance.

Now that you know this..

Let's choose our structure

Note: in each article of the series, there will be this part where I will create lore for an imaginary project. Any resemblance with an existing project is coincidental.

The Odyssey is a fictive project for which I will use the designing principle of The 12 Labors of Hercule.

In the myth written by Homer, The Odyssey, the structure used is the meandering one, like in The Iliad. Hercules and Achilles travel to a lot of places, encounter a lot of characters, and live a lot of adventures.

However, I won't use the same structure as my main inspiration and go for the linear one.

I want the project community to be involved in this story and follow Kyou in his adventure with enthusiasm. That's why I think that the best way to tell this story is by using the linear structure.

- Key point: there is no good or bad structure, there are only structures that will fit well or not with the story you tell.

To conclude..

Now that you know how to structure your story, we'll look at how to write characters in the next part: The Characters of Your Story - How to Apply Storytelling to Your Project, Part 4